Analysis and Review of Coaching Winter Track in Time of War Poem and the Big Scrum Book

Analysis of Coaching Winter Track in Time of War and the Big Scrum

Analysis and Review of Ehrhart’s “Coaching Winter Track in Time of War” Poem and the “Big Scrum” Book on Teddy Roosevelt and the early history of football.

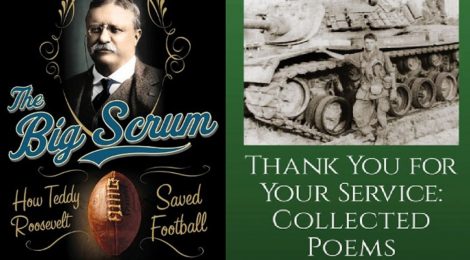

A poem by noted poet and Vietnam War veteran W.D. Ehrhart, titled Coaching Winter Track in Time of War, is an interesting work that combines the often militarized phrases in American sports with the reality of the thoughts of a war veteran. On a first reading of this poem, the reader will notice that the Track athletes are working out on a football field, and this invites comparisons to the book “The Big Scrum: How Teddy Roosevelt Saved Football,” by John J. Miller (a writer for the National Review). This is an interesting tale of the very early days of football, and how President Theodore Roosevelt, a life-long fan of the game, played a very important role in saving football from itself (the early days of the sport were very violent, and there were a lot of calls to ban football). But the part of the book that this poem reminded us of, was the intellectual foundation for the development of football, and to a degree, basketball and baseball into national pastimes. This intellectual foundation was/is called Muscular Christianity, which is defined as “a philosophical movement that originated in England in the mid-19th century, characterised by a belief in patriotic duty, discipline, self-sacrifice, manliness, and the moral and physical beauty of athleticism.” (from Wikipedia).

The leading elites of both the U.S. and the British Empire of the later 1800s believed that Christian faith was best exemplified (in men) through vigorous physical activity, and the self-discipline that came with athletic training and pursuits, led to moral, upstanding, and patriotic young men. The YMCA has its origins in this idea.

Teddy Roosevelt was raised in a household that firmly believed in this ideal, and his whole life is a testament to this, from his personal pursuit of “the strenuous life,” to his belief in a “muscular” America, that could figuratively and literally flex its muscles around the world. It is no coincidence that the apex of this belief came at the same time in American history that the U.S. expanded (through war and military presence) into the Caribbean, the Pacific, and East Asia. Beginning in the 1890s, America acquired Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines through war and military strength, and gained increased control and influence in Cuba, much of Central America, and China at this time.

But how does all this relate to the poem by Ehrhart? Upon reading his anti-war poem from 2005 (two years into the Iraq War) we see the embrace of the athletic training that many young people need to achieve self-discipline, but a marked rejection of the implied militaristic metaphors that adherents of “Muscular Christianity,” in particular someone like Theodore Roosevelt would advocate.

In the second stanza, Ehrhart states:

You could fall in love with boys

like these: so earnest, so eager, so

ready to do whatever you ask, so

full of themselves and the world.

“So eager, so ready, to do whatever you ask,” could as easily be a line out of a quote by Robert E. Lee or George S. Patton talking about their soldiers. It is no coincidence that the military prefers recruits who played team sports in High School, for their physical fitness as well as for their implied self-discipline and ability to function in a team environment.

In contrast to Teddy Roosevelt, who saw the fact of casualties in both football (18 players died due to football injuries in 1905 alone) and in war, as an acceptable cost of building strong men and a strong country, the coach in Ehrhart’s poem, reflecting on the “the young dead soldiers coming home each night in aluminum boxes,” feels sadness at the cost of war, as planeloads of flag-draped caskets made their way home from Iraq in the early years of that war.

The last stanza of Ehrhart’s poem contains a poignant reminder that some of his young athletes may end up serving in the military and that saddens him as, after ending Track practice, the coach sends his boys home leaving him to “stand alone in fading light while memory’s phantoms circle the track like weary athletes running a race without a finish line.”

This last line shows the coach’s thoughts (we assume here that the coach is a war veteran, like the poet), and as he stands there, seeing ghost-like images of his runners, he may also be seeing the ghosts of long-lost military buddies who never came home, or, perhaps, seeing mental images of his former athletes, who went on to war. The final line evokes a feeling that, like “athletes running a race without a finish line,” our soldiers are fighting a war that may never end. The concept of the “Endless Wars,” or as the Pentagon coined the phrase “The Long War,” the race, as it were, may never truly end.

Sidenote on that thought: A student who graduated from High School in 2002 (same school year as the 9/11 attacks and the start of our war in Afghanistan), they could easily have an 18-year old child who will graduate this year, and be eligible to enlist in the military and serve in the very same war! That is an example of how our current “endless wars” are indeed, now generational.