America’s Decision to Use Atom Bombs on Japan: Right or Wrong?

Truman’s Decision to Use Atom Bombs on Japan: Right or Wrong?

As the 75th Anniversary of the dropping of the Atomic Bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki comes in August of 2020, it is easy to look at the whole issue from the vantage point of several generations of separation from the horrible reality of a world war, but to truly understand what happened, we need to look at it from the point of view of the people who were dealing with that war on a day-to-day basis.

The war between America and Japan began on December 7, 1941, with the surprise Japanese attack on the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This attack shocked America from a complacency borne of being physically separate from the rest of the world, a world that was at that point in the throes of World War Two. The World War had begun in Asia in 1937 (Japan invaded China), and in Europe in 1939, (Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland), and, while maintaining technical neutrality, the U.S. had increasingly provided material and moral support for the nations under attack by the Axis of Germany, Japan, and Italy (primarily Britain and China). This support for China was one of the main reasons Japan felt they had to attack the U.S. in order to destroy the American Pacific fleet. Japan desperately needed more natural resources (oil, rubber, tin, iron, etc.) to continue their war in China, and the U.S. had imposed severe economic restrictions on selling these materials to Japan.

South of Japan, in the areas now known as Indonesia and Southeast Asia, lay many of the resources the Japanese needed. But these areas were controlled by foreign powers (France had Indochina/Vietnam, Britain controlled Malaya and Burma, the Dutch ruled Indonesia, and America controlled the Philippine Islands). The decision was made to seize these territories and use the resources to supply their military in order to further the Japanese war against China. This plan involved making war on Britain, France, and the Netherlands (Britain was fighting the Germans in Europe, while both France and the Dutch were under German occupation by 1941), as well as the neutral United States. Japan’s plans called for simultaneous attacks on the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor (to forestall the U.S. fleet from attacking Japanese forces), the British in Singapore, Malaya, and Hong Kong, the Americans in the Philippines, and the Dutch in Indonesia. French Indochina had previously been occupied in 1940 and 1941.

On December 7 and 8, 1941, Japan launched the attacks on the U.S. and the Europeans in Asia and the Pacific. Hitler’s Germany (an ally of Japan already), declared war on the U.S. four days after Pearl Harbor. America was now in the World War on the Allied side.

Over the course of the next four years, the War in the Pacific was waged in many amphibious landings on small Pacific islands occupied by Japanese garrisons. Slowly, American and other Allied forces pushed the Japanese military back toward the Home Islands. As the Americans learned, however, the Japanese were very brave and very fanatical soldiers. The Japanese military ethos of Bushido (or at least, the modern, militaristic version promoted by the war-time military), called for death before dishonor, and considered surrendering to the enemy to be an act of cowardice. Thus, very few Japanese troops surrendered. Most chose to fight to the death, or if faced with no other options, chose suicide over surrender. This belief system and the practical effects of trying to fight an enemy who did not fear death, led Allied planners to believe that an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands would result in massive casualties.

With this in mind, President Truman, in consultation with his military and political advisors, as well as with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, decided that he had no other choice but to use the newly developed atomic bombs on Japan. Germany had finally surrendered to the Allies in May, 1945, and plans were being made to defeat Japan.

The Battle of Okinawa, which raged for 82 days in the spring and summer of 1945, helped tip the decision toward using the atomic bombs. American casualties totaled 82,000. Nearly 400 ships had been damaged, and nearly 500 planes had been lost. Okinawa was a Japanese island, and the defenders fought harder to defend the Japanese homeland than ever before. Most shockingly, to the Allies, was the fact that thousands of Japanese civilians on the island chose suicide over surrender to the Allies. This, combined with knowledge that Japan was reinforcing the defenses of the Home Islands, including training civilians (women, children, and old men) to fight to the death, caused American military planners to predict U.S. casualties of at least 250,000, and possibly higher in an invasion of Japan. Besides the civilians being trained to fight, it was estimated that Japan had nearly 2.5 million troops on the Home Islands, with millions more in occupied China, Korea, Southeast Asia, and Indonesia.

Truman’s advisors looked over several options, including a demonstration of the new weapon on a deserted island, in order to frighten the Japanese, but this was rejected. Other possibilities included continuing the massive air raids and sea blockade of Japan, but there was no way to predict if that would force Japan to surrender. The ultimate goal, as Truman himself wanted, was to end the war as soon as possible, with the fewest casualties (to the Allies, primarily, but also he considered massive Japanese civilian deaths in an invasion).

As August, 1945 approached, Japan had put out feelers, hoping for an end to the war on their terms, primarily one that would let them claim they had not surrendered, and would allow the Emperor to retain his throne. The Potsdam Declaration by the U.S., Britain, and China had called for unconditional surrender, which turned out to be the end result for Germany. At this point in history, the U.S. and Britain knew that the atomic bomb project (the Manhattan Project) had produced working atomic bombs.

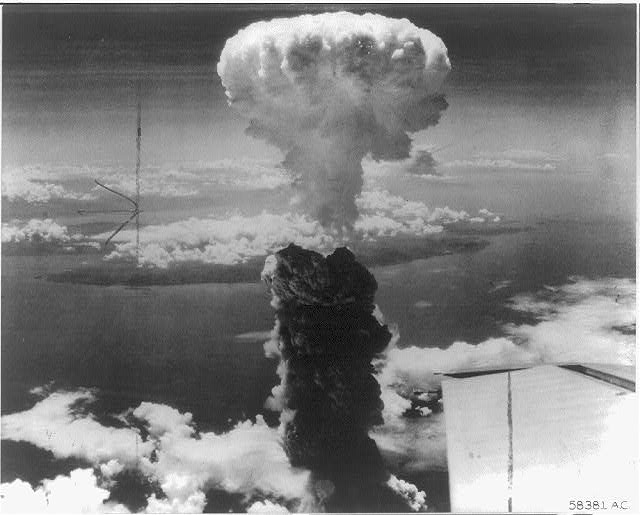

In the end, of course, Japan chose to ignore the Potsdam Declaration, and Truman felt he had no choice but to authorize use of the new atomic bombs. On August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb was used in war with the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki (that is also the day that the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan). Combined, these two atomic bombs killed nearly 200,000 people immediately, with hundreds of thousands more dying of the after-effects over the course of time. Even after the devastation of these attacks became clear, there were some in the Japanese military leadership who wanted to fight on. Finally, the Emperor of Japan, Hirohito, decided that Japan must surrender. He saw no way to fight this new weapon.

On August 15, 1945, Japan announced that they would surrender, and the formal documents of the Japanese surrender were signed on September 2, 1945.

Did Truman really have a choice? Not really. Had he allowed the war with Japan to drag on without using all available weapons to win, he would have been crucified by the American public. An invasion of Japan would have cost more American lives, and even a strict blockade of Japan to force surrender without an invasion would have continued to result in American casualties. If any good can be said to arise out of the two atomic bombings, it is that the effects of such weapons on people was well-documented, and even in the throes of the coming Cold War , atomic or nuclear weapons were never used. In addition, after the Japanese surrender, the Allies discovered that Japan was very low on food, and, had the U.S. imposed a strict blockade, in lieu of the atomic bombings, even more Japanese civilians could have perished.

For a detailed examination of the President’s decision-making process, we recommend the book Truman, by David McCullough

Please feel free to comment below.