|

Benedict

Arnold's Letter

To

The Inhabitants of America

|

|

Benedict

Arnold's Letter

To

The Inhabitants of

America

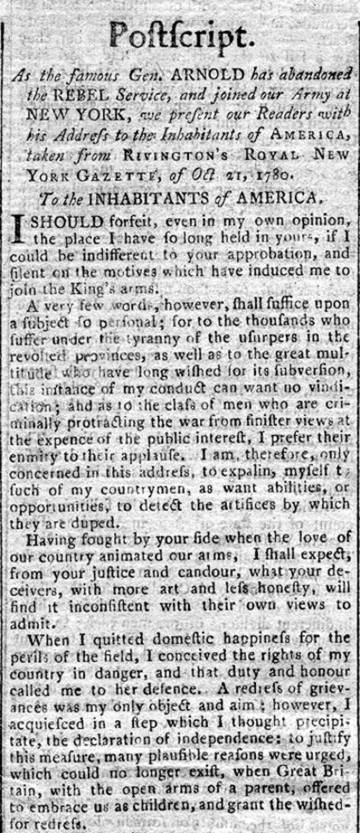

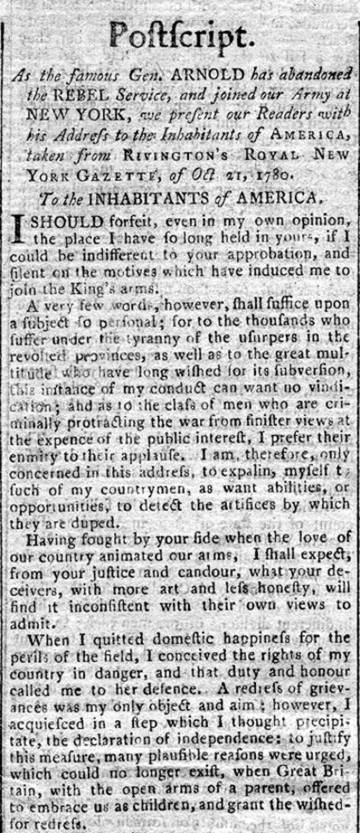

In

1780, prior to leaving America,

Benedict

Arnold

wrote a Letter to the Inhabitants of

America, in which he gave his reasoning

for his betrayal. This letter was

published in many American newspapers at

that time.

I should forfeit, even in my own

opinion, the place I have so long held

in yours, if I could be indifferent to

your approbation, and silent on the

motives which have induced me to join

the King's arms.

A very few words, however, shall

suffice upon a subject so personal; for

to the thousands who suffer under the

tyranny of the usurpers in the revolted

provinces, as well as to the great

multitude who have long wished for its

subversion, this instance of my conduct

can want no vindication; and as to the

class of men who are criminally

protracting the war from sinister views

at the expence of the public interest,

I prefer their enmity to their

applause. I am, therefore, only

concerned in this address, to explain,

myself to such of my countrymen, as

want abilities, or opportunities, to

detect the artifices by which they are

duped.

Having fought by your side when the

love of our country animated our arms,

I shall expect, from your justice and

candour, what your deceivers, with more

art and less honesty, will find it

inconsistent with their own views to

admit.

When I quitted domestic happiness

for the perils of the field, I

conceived the rights of my country in

danger, and that duty and honour called

me to her defence. A redress of

grievances was my only object and aim;

however, I acquiesced in a step which I

thought preciptate, the declaration of

independence: to justify this measure,

many plausible reasons were urged,

which could no longer exist, when Great

Britain, the the open arms of a parent,

offered to embrace us as children, and

grant the wished-for redress.

And now that her worst enemies are

in in her own bosom, I should change my

principles, if I conspired with their

designs; yourselves being judges, wsa

the war the less just, because fellow

subjects were considered as our foe?

You have felt the torture in which we

raised arms against a brother. God

incline the guilty protectors of these

unnatural dissentions to resign their

ambition, and cease from their

delusion, in compassion to kindred

blood!

I anticipate your question, Was not

the war a defensive one, until the

French joined in the combination? I

answer, that I thought so. You will

add, Was it not afterwards ncessary,

till the separation of the British

empire was complete? By no means; in

contending for the welfare of my

country, I am free to declare my

opinion, that this end attained, all

strife should have ceased.

I lamented, therefore, the impolicy,

tyranny, and injustice, which, with a

sovereign contempt of the people of

America, studiously neglected to take

their collective sentiments of the

British proposals of peace, and to

negociate, under a suspension of arms,

for an adjustment of differences; I

lamented it as a dangerous sacrifice of

the great interests of this country to

the partial views of a proud, ancient,

and crafty foe. I had my suspicions of

some imperfections in our councils, on

proposals prior to the Parliamentary

Commission of 1778; but having then

less to do in the Cabinet than the

field (I will not pronounce

peremptorily, as some may, and perhaps

justly, that Congress have veiled them

from the public eye), I continued to be

guided in the negligent confidence of a

Soldier. But the whole world saw, and

all American confessed, that the

overtures of the second Commission

exeeded our wishes and expectations;

and if there was any suspicion of the

national liberality, it arose from its

excess.

Do any believe were at that time

really entangled by an alliance with

France? Unfortunate deception! they

have been duped, by a virtuous

credulity, in the incautions moments of

intemperate passion, to give up their

felicity to serve a nation wanting both

the will and the power to protect us,

and aiming at the destruction both of

the mother country and the provinces.

In the plainness of common sense, for I

pretend to no casuistry, did the

pretended treaty with the Court of

Versailles, amount to more than an

overture to America? Certainly not,

because no authority had been given by

the people to conclude it, nor to this

very hour have they authorized its

ratification. The articles of

confederation remain still

unsigned.

In the firm persuasion, therefore,

that the private judgement of an

individual citizen of this country is

as free from all conventional

restraints, since as before the

insidious offers of France, I preferred

those from Great Britain; thinking it

infinitely wiser and safer to cast my

confidence upon her justice and

generosity, than to trust a monarchy

too feeble to establish your

independency, so perilous to her

distant dominions; the enemy of the

Protestant faith and fraudulently

avowing an affection for the liberties

of mankind, while she holds her native

sons in vassalage an chains.

I affect no disguise, and therefore

frankly declare, that in these

principles I had determined to retain

my arms and command for an opportunity

to surrender them to Great Britain; and

in concerting the measures for a

purpose, in my opinion, as grateful as

it would have been beneficial to my

country; I was only solicitous to

accomplish an event of decisive

importance, and to prevent as much as

possible, in the execution of it, the

effusion of blood.

With the highest satisfaction I bear

testimony to my old fellow soldiers and

citizens, that I find solid ground to

rely upon the clemency of our

Sovereign, and abundant conviction that

it is the generous intention of Great

Britain not only to leave the rights

and privileges of the colonies

unimpaired, together with their

perpetual exemption from taxation, but

to superadd such further benefits as my

consist with the common prosperity of

the empire. In short, I fought for much

less than the parent country is as

willing to grant to her colonies as

they can be to receive or enjoy.

Some may think I continued in the

struggle of these unhappy days too

long, and others that I quitted it too

soon-- To the first I reply, that I did

not see with their eyes, nor perhaps

had so favourable a situation to look

from, and that to our common master I

am willing to stand or fall. In behalf

of the candid among the latter, some of

whom I believe serve blindly but

honestly--in the bands I have left, I

pray God to give them all the lights

requisite to their own safety before it

is too late; and with respect to that

herd of censurers, whose enmity to me

originates in their hatred to the

principles by which I am now led to

devote my life to the re-union of the

British empire, as the best and only

means to dry up the streams of misery

that have deluged this country, they

may be assured, that concious of the

rectitude of my intentions; I shall

treat their malice and calumnies with

contempt and neglect.

New York, October 7, 1780. B.

Arnold

|

Copyright

© 1998-2011 Roger A. Lee and History Guy

Media; Last Modified: 07.18.11

"The

History Guy" is a Registered Trademark.

Contact

the webmaster

|